A Heart to Heart on Heritage Languages

PERSONAL STORY

By Anthony Burger & Rebecca Hall

Published May 4, 2024

This article is also available in: Italiano

There are over 7000 languages in the world and almost eight billion people who speak them. With so much diversity, combined with the globalization of modern life, it should come as no surprise that languages (and their speakers) can end up isolated and surrounded by speakers of another language.

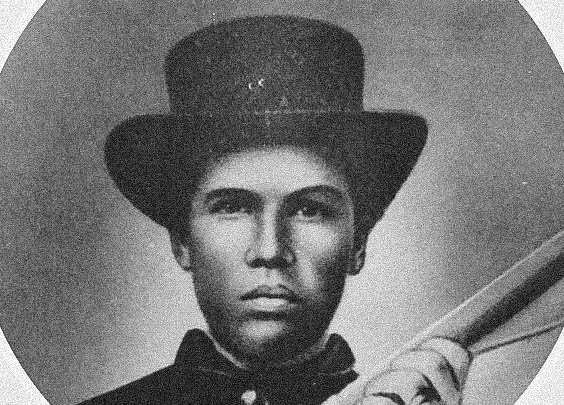

Rebecca Hall and their grandfather from the Cherokee side of the family. By his generation, the language had already faded away. His father was the last fluent speaker of Cherokee in the family, although his wife, despite being European, had some knowledge of it.

This diversity also leads to heritage speakers – people with a connection to a language other than the dominant one in their environment. Heritage speakers vary quite a lot – no two of them are alike! There are even several profiles of heritage speakers. Some learn to speak, read, and write their heritage languages, others may only speak their language, and still others may understand the language without speaking it – a phenomenon called passive or receptive bilingualism. By some definitions, the term “heritage speaker” even encompasses people who never had contact with a given language, but grew up connected to the language through family history, through a culture or a community that speaks it.

Linguaphile editors Anthony Burger and Rebecca Hall are both heritage speakers, but their backgrounds vary. In this conversation, they share their experiences, discuss their approaches to learning heritage languages, and consider what being a heritage speaker means to them.

ANTHONY

I grew up speaking a heritage language at home. My mom is Czech, my dad is American, and our household was always bilingual. I still speak Czech every day, although I wouldn’t consider myself quite at the level of a native speaker. What’s your heritage language background, Rebecca?

REBECCA

Several languages are technically heritage languages for me but I don’t view them all as such, because I’m learning them for different reasons. However, I didn’t grow up surrounded by any of them or only had minimal contact. Within my family history, we mostly know about ancestors who spoke German and Cherokee* fluently but never passed down the knowledge of the language to anyone else in the family. Despite this, some of my family did decide to pick up German for different reasons.

*Rebecca does not claim to be Cherokee Native American themself, as they were raised far from any federally recognized tribes and had no one teach them the culture growing up. Their interest in the Cherokee language and culture stems from family history and a desire to connect with and understand their ancestral roots.

So, despite having grown up speaking Czech, what makes you feel like you aren’t at the level of a native?

ANTHONY

Essentially, being a heritage speaker for me means that Czech has always been the language that I speak at home along with English. English has been dominant in my life ever since I started going to school in America and realized that it was the only language I could use with most other people. So there were a lot of things that I never learned in Czech because they weren’t accessible to me socially or through formal education. I can read Czech fairly easily, for example, but I can’t write it very well – and I didn’t learn the word “science” until I was 15!

In 2018, Anthony visited Házmburk castle in the Czech Republic. Recalling his younger days, he vividly remembers feeling frightened by the strong winds at the towering heights of the castle.

Beyond that, it’s possible to entirely forget a language you knew as a child. That didn’t happen to me, but there are definitely aspects of Czech grammar that have stopped coming as naturally as they used to.

You mentioned that you have some languages that were spoken in your family but you don’t consider them heritage languages. Why is that?

REBECCA

I am lucky enough to have people on both sides of my family who have mapped out our family tree and gone to extensive lengths to learn about our ancestry. Thus, I know that French and Scottish Gaelic are also technically heritage languages of mine.

However, I learned French mostly to prove to myself that I could – not because of my heritage. It is a similar situation with Scottish Gaelic: while I do plan to learn the language, it isn’t solely for heritage. The main reason I don’t consider either of these to be heritage languages is that both are just so far back in my family tree. We don’t know a lot about those people in general so I’m not emotionally attached to them. Meanwhile, I do have a lot of family stories about my relatives who spoke Cherokee* and German.

Photographs depicting Rebecca's Cherokee ancestors, whose lineage includes children who became the last Cherokee speakers in the family. Notably, the man in the image served in the Civil War.

ANTHONY

I have a similar relationship to Yiddish. My grandfather remembers visiting his grandmother and being unable to talk to her because she only knew Yiddish. But by his generation, nobody in my family knew the language even passively. After that much time, it feels like I’m too disconnected in time and culture to assert a relationship to the language, even though every ancestor on my one side of my family spoke it just a few generations ago.

Learning a heritage language can bring up all sorts of emotions (I know it does for me). What does it feel like to be in contact with heritage languages for you?

REBECCA

I think emotions are a big factor in learning any language, but with heritage languages, I feel like it goes deeper because of the personal connection and history with the language. I grew up with minimal contact with German, learning a few curse words and how to order a beer. Ironically it wasn’t the German side of my family but the side that I had strained relationships with who taught me and as a result I have struggled to get past the beginner stage. The language somehow feels more daunting than even Japanese.

Despite that, there is a special place in my heart for the German language. I have very fond memories of being completely enchanted by my great grandma’s German books as a kid. It seemed like they held magical secrets that could only be unlocked if I learned the language. However, learning the language has involved facing my demons, which takes patience and kindness towards oneself. There are obviously many layers to this, and due to a lot of generational trauma, learning German comes with its own weight.

A German prayer book, handed down by Rebecca’s great-grandmother, bears the inscription in German: "Memory of the first Holy Communion for [blurred for privacy reasons] — Newburg, Wis., 3rd Oct. 1909."

Like German, there is a lot of trauma tied to Cherokee as well. Learning it became a way to reclaim family history that some members of my family had previously belittled and shamed. While it is an endangered language that comes with challenging grammar, I have had the most heart-warming experiences with native speakers of Cherokee. I will never forget the sparkle in their eyes when I try to speak and use the language even when I stumble over my words and struggle to use the proper tone.

ANTHONY

My heritage language also feels emotionally charged. I often feel like I’m somewhere between being Czech and being a foreigner. I can usually pass for a native speaker for a while before I slip up or forget a word. This sometimes makes me worry whether people will think of me as a Czech incapable of correctly speaking my own language or as a foreigner who has done an impressive job of learning.

Karlštejn castle, located in the Czech Republic, holds special significance for Anthony as it was the venue where his parents got married.

But I’m also so thankful for the relationships and experiences that Czech has let me have – it’s the language I tell my grandmother I love her in, and my favorite childhood films are all in Czech (Give the Devil his Due holds a special place in my heart). Knowing Czech, even imperfectly, also opens doors for me in terms of travel, education, and literature. It’s thanks to Czech that I’m interested in Slavic studies and even pursued a degree in linguistics. The more I use Czech for what I’m passionate about, the better I get.

Do you have any advice for people approaching their family’s heritage languages?

REBECCA

Be kind to yourself! Learning a heritage language can involve traversing years of trauma, generational and otherwise. There will be times when things get emotional, learn to sit with the emotions, but stay grounded in the reasons you started learning the language.

Outside of that, a lot comes down to which language you are learning and whether it’s endangered or not, what level you are, and how many resources are available. I think my biggest piece of advice would be to find a community where you can support each other as you learn. Maybe see if you can convince someone to learn the language with you so you can cheer each other on. Having friends who understands the demons you are confronting can be incredibly helpful in keeping you motivated even when the going gets tough. If you get stuck, you can problem-solve together and find other ways to learn the information or find a different method that helps you more.

You also need to learn to be okay with making mistakes, even if they’re embarrassing and make you want to hide away for the next century! Sometimes in language learning you have to make those embarrassing mistakes so you finally learn the difference between two words that you keep confusing. The discomfort you felt will fuel your memory of the correct usage. Mistakes help you move forward, become more resilient, and help you learn to laugh at yourself so you can let things go more easily.

Would you have anything to add?

ANTHONY

In my case, my learning journey doesn’t begin at the beginning. So I’ve had a few different things to keep in mind!

Unlike English, Czech has a very stark difference between the standard language and the way people speak. This affects a lot of the language – there are some differences in noun endings, conjugations, and even a lot of vowels are different in spoken Czech (at least in the dialect I speak from Bohemia). For me, being a heritage speaker means coming into contact with and learning a more formal form of the language than I’m used to. And that’s a fairly common issue with heritage languages! So it’s been important for me to keep in mind that sometimes the way I say things isn’t wrong, it’s just not standard.

Page from the back of an old family prayer book recording weddings, births, deaths, and notably also the First World War.

I also wish someone had told me sooner that I should dive into things I’m interested in. For a long time, I thought I needed to read children’s books in Czech because they’re easier. That wasn’t easier for me at all! To be honest, I properly started reading Czech when I found a community on tumblr with Czech memes. From there I went straight to reading fantasy, memoirs, and whatever would have also interested me in English. Sure, I might not understand everything, but it gets me hooked and keeps me going!

It’s also worth mentioning that growing up around a language, even if you don’t speak it, can help you (re)learn a heritage language. Studies have shown that people relearning a language they once spoke learn the differences between sounds faster, acquire a more native-like accent, and even use more native-like structures. Learning a language will still require a lot of elbow grease, but it’s important to know that forgotten things are never gone – just sleeping. If you’re in this position, you might like Marissa Blaszko’s YouTube channel Relearn A Language about relearning Polish as a passive bilingual heritage speaker. Her content has been really inspiring for me personally, even though I’ve never forgotten how to speak Czech.

Heritage language learners can have vastly different experiences with their languages. Language can be a profound way for heritage speakers to connect with themselves, their past, and their family. In some cases, a person’s language background can significantly alter their learning journey. This may mean starting as an advanced speaker or starting with nothing but wanting to learn a particular non-standard dialect their family spoke. Every heritage speaker is unique and valid, whether they grew up with the language like Tony or started learning it much later in life like Rebecca.

Written by

Edited by

Alice Pol, Aline Vitaly, Anna Sulaiman & Marvin Nauendorff

Cite This Article

Burger, Anthony, and Rebecca Hall. 2024. "A Heart to Heart on Heritage Languages." Linguaphile Magazine, May 4.

https://linguaphilemagazine.org/editorial/a-heart-to-heart-on-heritage-languages.

FURTHER READING

Krashen, Stephen. "Language shyness and heritage language development." In Heritage language development, 41-49. 1998.

PDF (focused on difficulties faced by heritage speakers in approaching their heritage languages)"Who Are Heritage Learners?" Institute for Language Education in Transcultural Context. Accessed April 6, 2024.

Link (focused on teaching heritage L1 speakers)Relearn a Language. Accessed April 6, 2024.

Link - Marissa Blaszko talks about relearning her native language, Polish, and gives advice.Sedivy, Julie. Memory Speaks. Belknap Press, 2021.

Amazon - Julie Sedivy combines linguistic research about heritage languages with her personal experiences as a heritage speaker of Czech.Sedivy, Julie. "The Strange Persistence of First Languages." Nautilus Magazine on Medium, March 18, 2019. Accessed April 6, 2024.

Link - shorter article by Julie Sedivy.Meraji, Shereen Marisol, and Audrey Nguyen. "How To Learn A Heritage Language." WBUR on NPR. Updated December 21, 2022. Accessed April 6, 2024.

Link - article about various people’s (including the author’s) experiences with heritage languages + language learning advice for heritage speakers.

Bibliography

Au, Terry Kit-fong, Leah M. Knightly, Sun-Ah Jun, and Janet S. Oh. 2002. "Overhearing a language during childhood." Psychological science 13, no. 3: 238-243. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=edf7524aa1e53fdb675a5137d63b36e60686da90.

Au, T. K., J. S. Oh, L. M. Knightly, S. A. Jun, and L. F. Romo. 2008. "Salvaging a Childhood Language." Journal of Memory and Language 58, no. 4: 998-1011. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2390909/.

Blaszko, Marissa. 2021. "Heritage Speakers’ Pantry [10 Student Resources]." Relearn a Language. October 27. Accessed April 6, 2024. https://relearnalanguage.com/heritage-speakers-student-resources/#DBT-Skills-for-Heritage-Speakers.

Eva, Amy L. 2017. "Why We Should Embrace Mistakes in School." Greater Good Magazine. November 28. Accessed April 6, 2024. https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/why_we_should_embrace_mistakes_in_school.

Isurin, Ludmila. 2000. “Deserted Island or a Child’s First Language Forgetting.” Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 3, no. 2: 151–166. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728900000237.

Kelleher, Ann. 2010. "What is a Heritage Language?" Center for Applied Linguistics. Accessed April 6, 2024. https://www.cal.org/heritage/pdfs/briefs/What-is-a-Heritage-Language.pdf.

Nekvapil, Jiří. 2015. "Ferguson’s ‘Diglossia’ in the Discourse of Czech Linguistics" Presented at Globalizing Sociolinguistics, 18-20 June. Accessed April 6, 2024. http://languagemanagement.ff.cuni.cz/system/files/documents/Nekvapil_Leiden_2015.pdf.

Singh, L., Liederman, J., Mierzejewski, R., and Barnes, J. 2011. "Rapid reacquisition of native phoneme contrasts after disuse: you do not always lose what you do not use." Developmental Science 14: 949-959. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7687.2011.01044.x.

"S certy nejsou zerty." Directed by Hynek Bocan. 1985. IMDb. Accessed April 6, 2024. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0087731/.

101languages. "Dialects of the Czech Language." Accessed April 6, 2024. https://www.101languages.net/czech/dialects.html.

Relearn a Language. YouTube. Accessed April 6, 2024. https://www.youtube.com/@relearnalanguage.