Design for Language, Language of Design

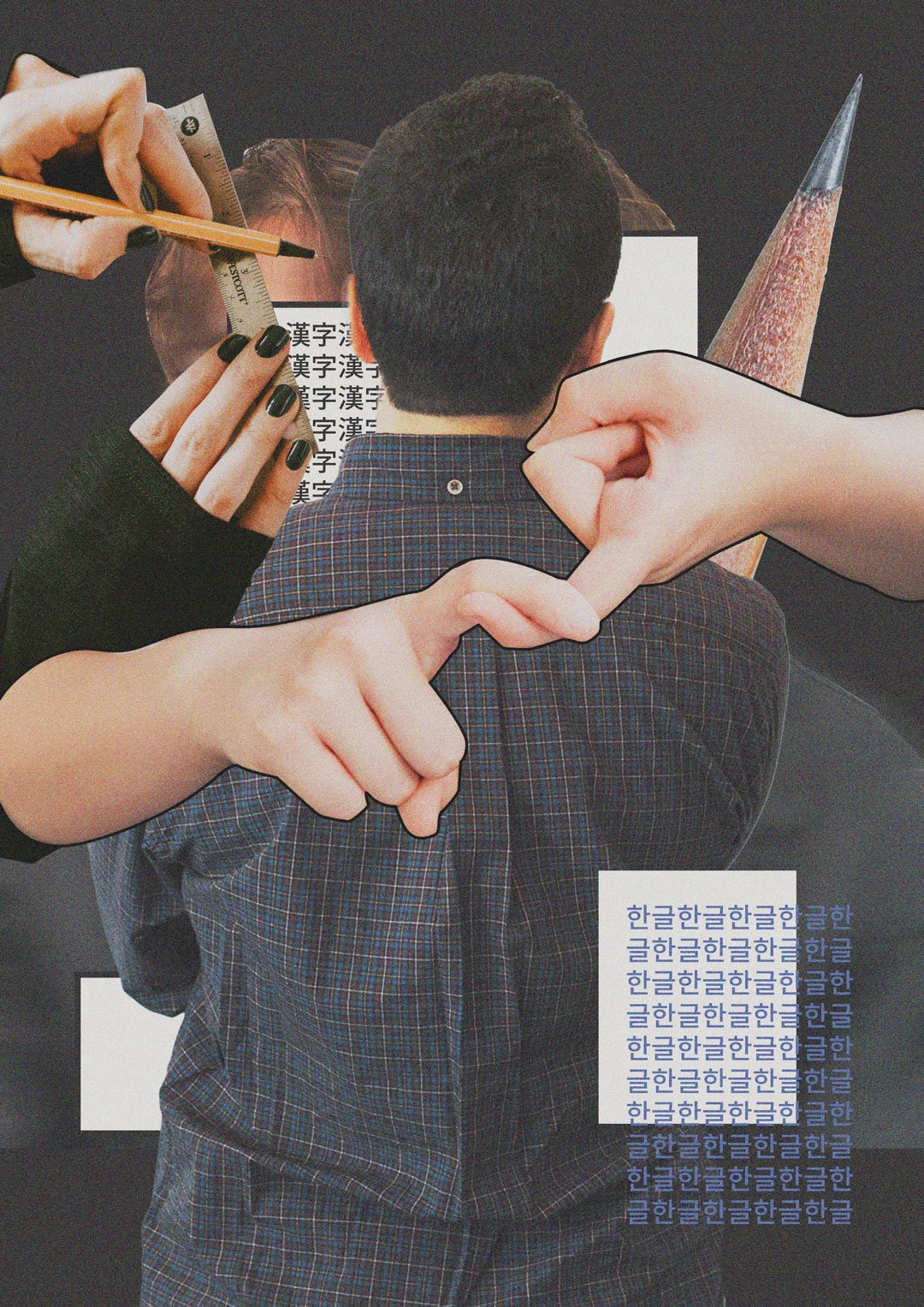

Image created by Linguaphile Magazine from photos by Kelly Sikkema, TJ Cosgrove, Christina Morillo, Marvin Nauendorff, and RDNE Stock Project.

In the words of Inuk author Rhoda Kaukjak Katsak, the Saqiyuq is described as "a wind that blows across the land or ice, a strong wind that suddenly shifts its direction but still maintains its force." While I'm not comparing myself to such a majestic force of nature, I must admit I can relate to how the Saqiyuq might feel. Since I was young, I've been fascinated by a variety of subjects and had just as many aspirations for my future. Would I become a physics teacher, a museum curator, a documentary photographer in the Arctic, a musician, or perhaps a tailor? Every few months, my life's ambition seemed to shift to something new. Though my goals have evolved over time, my curiosity remains constant.

Upon reflection, I realized that a common theme ran through all my pursuits: a desire to connect with others. Whether teaching, curating, capturing images, making music, or making clothes, my underlying motivation has always been to express what excites me. Gradually, these dreams and aspirations merged into a single idea—a distilled notion of communication itself. My ultimate goal became clear: to communicate what communication is all about. Language.

LANGUAGE AS ESCAPISM

The first time I actively decided to study a foreign language was during a family vacation in Sweden. Yet unexpectedly, instead of immersing myself in Swedish, I made the spontaneous decision to tackle Mandarin Chinese. I vividly recall sitting on the bed with my brother, munching on a peculiar variety of potato chips not found in Germany, as we repeated phrases over and over, almost in a friendly competition with each other. "Zhè gè nán rén shì zhōng guó rén. Nǐ huì shuō zhōng wén má?" — "This man is Chinese. Can you speak Chinese?" — became our mantra. However, after a few weeks, laziness crept in, and the initial fascination waned.

It wasn't until a few years later, when I discovered that Japanese shares characters with Chinese, that my interest was reignited. Admittedly, I was also seeking a distraction from studying for the Abitur, the German high school final exam. I found myself spiraling into the world of language learning advice, delving into words, characters, grammar, and the plethora of opinions on various topics.

Instead of focusing on the theory of relativity in class or absorbing my history teacher's lessons on the Soviet Union, I found myself reviewing Japanese vocabulary and studying grammar.

Though opting to prioritize Japanese over my academic studies may have seemed foolish at the time, it ultimately proved to be one of the most rewarding decisions of my life.

Aside from everything else on my mind, pursuing language studies or a career involving languages was never something that entered my thoughts. In fact, after bringing home my fourth consecutive F in Spanish during 8th grade, my teacher bluntly suggested that perhaps languages weren't my forte. That moment left a lasting impression, convincing me that I lacked the intelligence to grasp a foreign language or that my brain functioned differently from those of the straight-A students who seemed effortlessly fluent.

Throughout my later school years, I increasingly felt isolated from my peers and trapped in my small German countryside town. However, when I discovered my interest in Japanese toward the end of high school, connecting with Japanese speakers and delving deeper into the culture, a desire to break free from my surroundings intensified. This longing was actualized through a volunteer opportunity at a care facility in Osaka.

The author at the Peace Memorial Park in Hiroshima, Japan, where he met with Keiko Ogura, a survivor of the Hiroshima atomic bombing, author of several books and founder of the Hiroshima Interpreters for Peace (HIP).

Obtaining the necessary visa proved to be a daunting challenge amidst the strict immigration policies of the pandemic era. Nevertheless, I persevered through numerous obstacles and bureaucratic hurdles, eventually finding myself in Osaka. With determination and grit, I threw myself into my work, giving my all to carve out a fresh start and embrace the opportunity to begin anew. However, pouring myself entirely into my work eventually took its toll on my health, leading to a rapid decline. Eventually, I had no choice but to resign from my position at the care facility.

It was a setback that forced me to hit the reset button on my life once again. Yet, amidst this change, I found myself revisiting the world of design.

During my time in Japan, I had become deeply involved in Osaka's local indie music scene, forging connections with numerous musicians and artists. This rekindled my passion for design, which I had set aside before my flight to Japan. I began creating album covers and merchandise designs for various bands, and even dabbled in clothing design. Through this process, I realized that design could serve as a powerful means to express my passions and contribute something meaningful to the world. The Saqiyuq in me was changing its course.

The realization that studying Japanese had led me to this pivotal decision prompted me to explore other languages with newfound enthusiasm. What other epiphanies lie behind the unlocked doors of each language? I was curious. I started with Korean, Norwegian, and Vietnamese, but soon delved into languages like Inuktitut, Ainu, and Okinawan—endangered languages spoken by only a handful of people worldwide, fighting for survival. It struck me then: who was championing the cause of these languages, supporting their preservation and revitalization?

It was communicators, designers of typefaces and fonts, creators of keyboard layouts, and developers of learning websites and educational content. These individuals were using design to safeguard languages.

Kinjo Stone Road in Okinawa, Japan, where the author had the opportunity to explore and immerse himself in Shuri Okinawan and the Okinawan-Japanese dialect. (Photo taken by the author)

While I had previously believed that medical design was the sole field capable of directly impacting people's health, I came to understand that linguistics communication design holds equal power, and perhaps even more. Language is intertwined with culture, and culture is essential to wellbeing. This shift in perspective took me from moments of self-doubt and giving up on languages to the creation of Linguaphile magazine. Here, I have the privilege of being part of a team of eight talented editors, writers, designers, and linguists. Together, we communicate the stories of the individuals behind languages and those who work tirelessly to keep them alive, all through visual design in a non-profit medium.

Designers have the power to make a tangible impact in safeguarding cultural heritage and promoting inclusivity.

Perhaps, in embracing the fluidity and adaptability of the Saqiyuq, we find strength in our ability to shift direction while maintaining our force. In celebrating the uniqueness and autonomy of each language and culture, we contribute to a more vibrant and interconnected global community. We should continue to follow the Saqiyuq, designing new paths and advocating for a world where linguistic diversity is not only accepted but celebrated.

Written by

Edited by

Cite This Article

Nauendorff, Marvin. 2024. "Design for Language, Language of Design." Linguaphile Magazine, May 5. https://www.linguaphilemagazine.org/editorial/design-for-language.

Bibliography

Wachowich, Nancy, Apphia Agalakti Awa, Rhoda Kaukjak Katsak, and Sandra Pikujak Katsak. 1999. Saqiyuq: Stories from the Lives of Three Inuit Women. Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press.

https://www.mqup.ca/saqiyuq-products-9780773522442.php.