Script as a Cultural Lifeline: The Untold Story of Canada’s Indigenous Writing System

Written by Marvin Nauendorff

Published April 2, 2024

This article is also available in Deutsch, 日本語.

Naulaq LeDrew (ᓇᐅᓪᓚᖅ ᓕᑐᕈ) during the filming of "I AM NAULAQ," a short film directed by Avatâra Ayusohree in Iqaluit, Nunavut, 2018.

(Avatâra Ayusohree, Three Women Three Films, used under Canadian Fair Dealing law)

When asked why it matters to preserve her language, Inuktitut, Naulaq LeDrew (ᓇᐅᓪᓚᖅ ᓕᑐᕈ,) an artist, elder, and pivotal member of the Toronto urban Inuit community, replies as if the answer is self-evident: "It's important to me because I am alive. ᐃᓅᒐᒪ, ᐃᓅᒐᕕᑦ. Because you are alive." Throughout an interview conducted by the non-profit organization Tungasuvvingat Inuit, she communicates in a blend of English and Inuktitut. Similarly, both the question and her name, along with the subtitles, are presented in Canadian Aboriginal Syllabics, Inuktitut's writing system.

“ᐃᓅᒐᒪ, ᐃᓅᒐᕕᑦ. ”

Her response underscores a profound truth: the preservation of her language is not merely a linguistic endeavor but a testament to the vitality and resilience of her people. Contrary to widespread misconceptions, the Inuit communities are far from extinct; they are vibrant and flourishing. When one types Inuit into a search bar, the majority of the results that appear are black and white photographs dating back to the early 20th century. European explorers captured these images, which were intended for European audiences and inadvertently contributed to the outdated perception of Inuit cultures. However, the reality is quite different. Today, the Inuit are a dynamic population of over 150,000 individuals, residing throughout the Arctic regions, from Alaska to Greenland. The vibrant population of the Inuit is mirrored by the rich diversity of languages they speak.

The critical importance of preserving endangered languages, such as Inuktitut, is a focal point in both linguistics and cultural studies. Canadian Aboriginal Syllabics (CAS), often shortened to just Syllabics, have a fascinating role in these efforts. These are a unified group of writing systems including the symbols used to write Inuktitut. They serve as vital lifelines to several Indigenous languages, connecting past, present, and future generations.

1946. Historic image of a group of Inuit standing outside near their tupiit (tents), Pangnirtuuq, Nunavut.

(George Hunter. National Film Board of Canada. Library and Archives Canada)

1915. Historic image of a group of Inuit in their village near Coppermine River, Nunavut.

(Frits Johansen, Canadian Museum of History.)

Canadian Aboriginal Syllabics

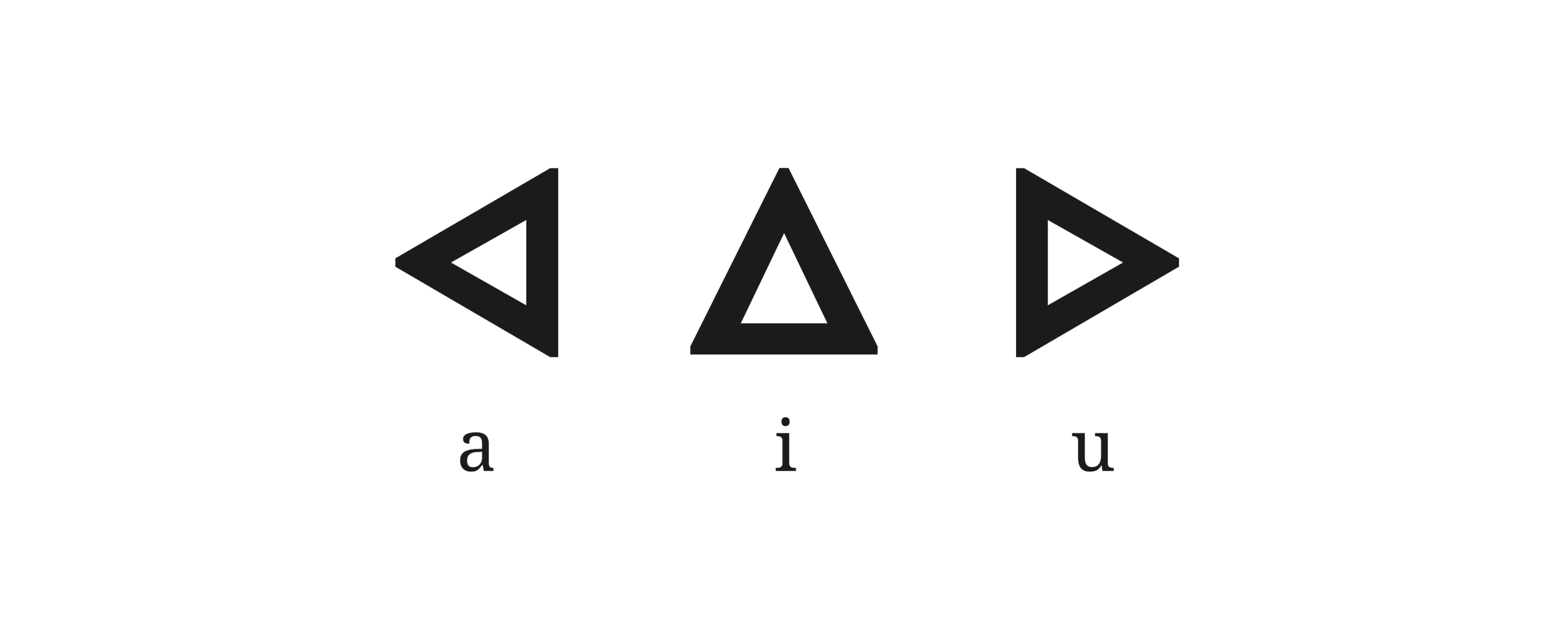

Canadian Aboriginal syllabics (CAS) refer to a type of writing system used for several Indigenous Canadian languages, including Nêhiyawêwin (Cree), Inuktitut (Inuktut), Anishinaabemowin (Ojibwe), Dakelh (Carrier), iyuw iyimuun (Naskapi), and Saı́yısı́ dëne (Sayisi Dene). These writing systems are known as abugidas. In an abugida, each symbol typically represents a combination of a consonant and a vowel. However, unlike syllabaries, where each possible combination of consonant and vowel has its own unique symbol, in abugidas, the consonant symbols are modified to indicate different vowels. What's special about CAS is the way vowels are shown by changing the orientation (the direction the symbol faces) of the consonant symbol. This method of showing vowels by rotating the consonant symbol is unique to Canadian syllabics.

If we take Inuktitut as an example, each of the 14 consonant sounds in the language is matched with a syllabic character. This character changes form—through rotation or reversal—to signify one of the three vowel sounds (i, u, a). For example, ᕙ represents 'va', ᕕ represents 'vi', and ᕗ represents 'vu'. If we change the consonant to 'n', it would look like this: ᓇ stands for 'na', ᓂ stands for 'ni', and ᓄ stands for 'nu':

When vowels occur without a preceding consonant, specific characters are used: ᐊ for 'a', ᐃ for 'i', and ᐅ for 'u':

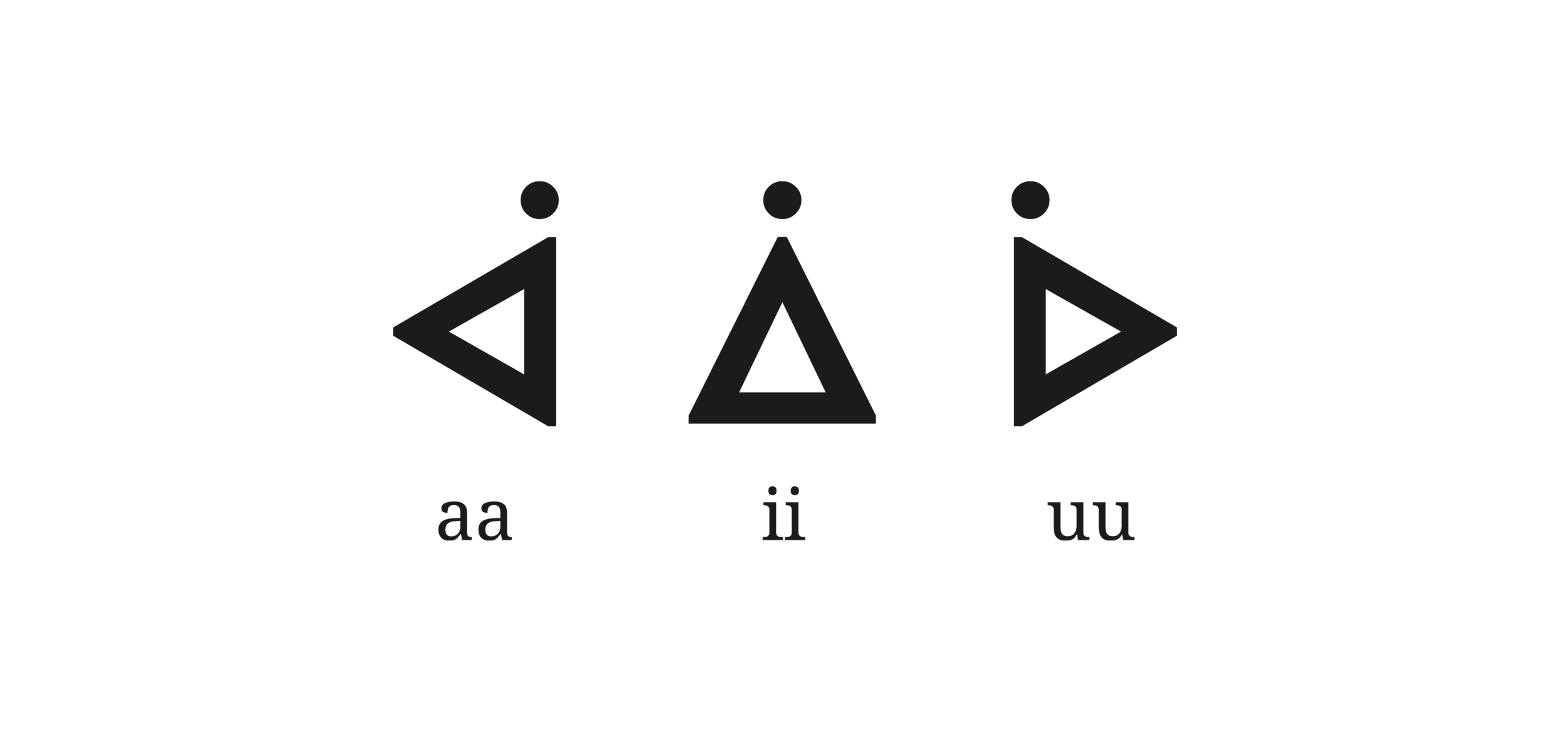

Inuktitut extends vowel sounds by adding a dot above the character, equivalent to doubling the vowel in Latin writing. ᐊ (a) becomes the lengthened ᐋ (aa) when adding a dot above it. In the same way, ᒥ (mi) becomes ᒦ (mii), ᑕ (ta) extends to ᑖ (taa) and so on:

Consonants that are not followed by a vowel use smaller 'final' characters, which are written as the consonant shape in superscript. For instance, if ᐸ refers to 'pa', then ᑉ stands for 'p'. Although this is the case in Inuktitut, the shapes of final consonants vary from language to language.

Some characters look more complex but represent single syllables, such as 'qi', 'qu', 'qa' (ᕿ, ᖁ, ᖃ), and the 'ng' row 'ngi', 'ngu', 'nga' (ᖏ, ᖑ, ᖓ). Additionally, syllables like 'nngi', 'nngu', 'nnga' (ᙱ, ᙵ, ᙳ), and syllables that begin with a double 'q' consonant, like 'qqi', 'qqu', 'qqa' (ᖅᑭ, ᖅᑯ, ᖅᑲ) have their own characters:

These syllabic characters and consonant finals get combined to represent the sounds of Inuktitut. Latin based interpuncation marks like '?', '!' and '.' are used and spaces are put in between words. However, in Inuktitut, spaces do not appear as often as in other languages. Inuktitut is a polysynthetic language. That means that words are constructed through attaching different units of meaning to each other. Because of this, single words in Inuktitut can get quite long. A word in Inuktitut that captures the meaning of a full sentence in English might look like this:

“Inuktituusunguvit?” meaning “Do you speak Inuktitut?”. To distinguish the different syllables, they are marked in blue and black.

To get a better idea of how syllabic writing might look in an everyday scenario, here is an example of an excerpt of a news report about a figure skating duo from Nunavut written in Inuktitut Syllabics:

ᓄᓇᕗᒥᑦ ᐅᓄᙱᓛᑦ ᐱᙳᐊᕆᐊᖅᑐᖅᑐᓂ ᐅᑭᐅᖅᑕᖅᑐᕐᒥ ᐅᑭᐅᒃᑯᑦ ᐱᙳᐊᕕᒡᔪᐊᕐᓇᒥ ᓯᐊᕐᕆᔭᐅᑎᖏᓐᓂᒃ ᐊᑎᕗᑦ ᒫᔅᓯ 15ᒥ ᑭᖑᓪᓕᖅᐹᒥ ᖁᙱᐊᖅᑕᐅᓂᐊᖅᖢᑎᒃ. ᐃᖃᓗᖕᓂ ᓄᓇᖃᖅᑑᒃ ᑎᐊ ᑭᓚᐸᒃ ᐊᒻᒪ ᑭᒻᐳᓕ ᒋᓯᖕ ᓯᐊᕐᕆᔮᖅᑐᓂ ᖁᙱᐊᖅᑕᐅᔪᒃᓴᓂ ᐃᓚᐅᔪᑑᓚᐅᖅᑑᒃ ᑭᒡᒐᖅᑐᐃᓪᓗᑎᑦ ᓄᓇᕗᒥᑦ ᐅᕙᓂ ᒫᑦ-ᓲ ᕚᓕ, ᐊᓛᔅᑲᒥ ᑕᕝᕙᓂ 2024ᒥ ᐱᙳᐊᕕᒡᔪᐊᕐᓇᖃᖅᑎᓪᓗᒋᑦ. ᑕᒪᕐᒥ ᐊᕐᓈᒃ ᓯᕗᓪᓕᖅᐹᑦᑎᐊᕐᒥ ᐱᒡᒍᓴᐅᑎᖃᑕᐅᓚᐅᖅᑑᒃ ᓯᐊᕐᕆᔭᐅᑎᓂ ᐊᑐᖅᖢᑎᒃ ᖁᙱᐊᖅᑕᐅᓪᓗᑎᒃ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᖁᙱᐊᖅᑕᐅᕝᕕᓪᓚᕆᖕᒦᖢᑎᒃ ᑲᓇᑕᐅᑉ ᓯᓚᑖᓂ.

“ᐊᔪᕈᓐᓃᖅᓴᖅᑎᑦᑎᔨ ‘ᐅᐱᒍᓱᑦᑎᐊᖅᑐᖅ’ ᐃᓚᒌᑦ ᓄᓇᕗᒥᑦ ᐅᓄᙱᓛᑦ ᐱᒡᒍᓴᐅᑎᔪᓂᒃ” by Madalyn Howitt on Nunatsiaq News. 2024.

Why not Use the Latin Alphabet?

The consideration of transitioning from CAS to the Latin alphabet for languages like Nêhiyawêwin (Cree), Ojibwe and Inuktitut is filled with cultural and linguistic implications. Some people argue that the Latin alphabet offers a more precise representation of speech sounds. This could potentially enhance literacy and aid in the preservation of these languages by distinguishing subtle differences that Syllabics may overlook.

However, significant concerns arise with this potential shift. Moving to the Latin alphabet could dilute the rich cultural identity inherent in Syllabics and align Indigenous languages more closely with dominant Euro-Canadian linguistic norms.

The debate is about more than linguistic accuracy; it's about balancing the benefits of a standardized Latin alphabet against the risk of cultural homogenization. It sheds light on a broader challenge: how to modernize and preserve Indigenous languages without compromising their unique cultural and linguistic heritage. As communities contemplate this shift, the focus remains on ensuring that any change in writing supports the broader goals of cultural preservation and self-determination.

A Short Account on History

The journey of the Canadian Aboriginal Syllabics (CAS) began in the early 1800s, marking the Nêhiyawak, often referred to as Cree in English, as pioneers in adopting a written form for their language Nêhiyawêwin (ᓀᐦᐃᔭᐍᐏᐣ). The Nêhiyawak, varying by tribe, use different names for themselves, with Nêhiyawak seemingly being the most widespread. They reside in the Subarctic areas stretching from Alberta to Quebec, and in some Plains regions of Alberta and Saskatchewan. The Nêhiyawêwin writing system later evolved into today's CAS. It blossomed across territories from Northern Québec to Northeast British Columbia in Canada and reached down to Montana. In fact, by the late 19th century the Nêhiyawak had achieved what may have been one of the highest rates of literacy in the world. It thrived until the English language's spread led to a decline in its use. However, the story didn't end there: a revival in recent years has rekindled interest in CAS.

There are two vastly different narratives detailing the origin of the Nêhiyawêwin Syllabics. On one side, Reverend James Evans, a Christian missionary, is often celebrated for creating the syllabary in 1840. It's said that he drew inspiration from the simple shapes of Pitman Shorthand, a widely used stenography system of that era. His remarkable feat of printing 300 copies of a Christian hymn in Nêhiyawêwin Syllabics is well-documented. Yet various Indigenous oral traditions offer a contrasting view, portraying the syllabary as a sacred gift from the Creator, Kisemanito. This version of the story, featuring Nêhiyawak Elders Mistanaskowew and Machiminahtik, brings a spiritual dimension to CAS origins and challenges the missionary narrative.

Tapatai (ᑕᐸᑕᐃ), assistant to Reverend W. James. The name Tapatai is said to be derived from Starboard Eye, a nickname given to Inuit by American whalers. 1946.

(S. J. Bailey. Library and Archives Canada)

Anglican missionary Reverend W. James teaching his class of Inuit students how to read Inuktitut syllabics, Qamanittuaq, Nunavut, 1948.

(S. J. Bailey. Library and Archives Canada)

The influence of these Syllabics extends to other Indigenous groups in Canada beyond the Nêhiyawak community. In the mid 19th century, missionaries adapted the syllabary for the Inuktitut language. Inuktitut is a key Inuit language in Canada, mainly spoken across the northernmost areas.

How Syllabics Preserve Culture

Canadian Aboriginal Syllabics (CAS) are more than just writing: In the bustling modernity of Canada's cities and the quiet, snow-blanketed landscapes of its northern communities, CAS is a bold declaration of Indigenous presence and identity. These Syllabics help keep traditions, stories, and languages alive, bridging past and present generations. They are especially crucial in a world where globalization threatens to erase unique cultural identities.

In recent years, several communities have started affectionately referring to their entire language as just "Syllabics" in English, a term that captures their deep connection to these symbols.

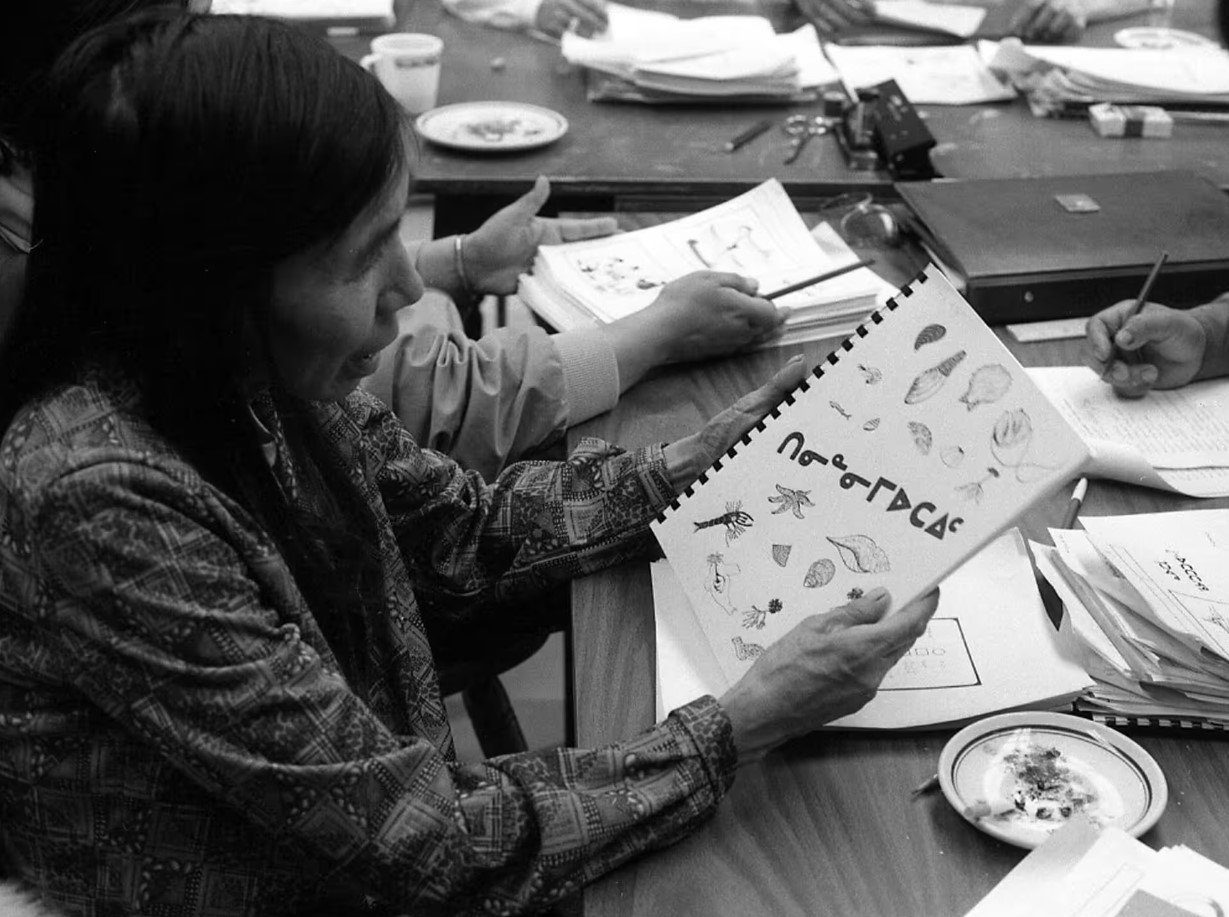

Mitiarjuk Nappaaluk (ᒥᑎᐊᕐᔪᒃ ᓇᑉᐹᓗᒃ) shows an Inuktitut booklet during an adult education work session in 1983.

(Tommy George Etok/Avataq Cultural Institute, used under Canadian Fair Dealing law)

Mitiarjuk Nappaaluk (ᒥᑎᐊᕐᔪᒃ ᓇᑉᐹᓗᒃ), a famous Inuk author, was a pivotal figure in the resurrection of CAS and her writings showcase its immense value. She used Syllabics to share her community's stories, traditions, and worldview. She gained recognition for authoring Sanaaq (ᓴᓈᕐᒃ), one of the first novels written in Inuktitut. Nappaaluk also translated literature into her language and assisted in compiling an initial Inuktitut dictionary. She later educated others on Inuit heritage and dialects in the Nunavik region and produced 22 publications for educational purposes. Her efforts and writings were dedicated selflessly to the future generations of Inuit. Even today, Nappaaluk’s storytelling continues to offer insights into the Inuit way of life, making her literature a vital part of cultural preservation.

The relationship between Indigenous communities and CAS, however, is complex. Initially introduced under colonial influences, CAS's roots present a paradox in their acceptance as Indigenous symbols. Despite these origins, Indigenous communities have reclaimed CAS, transforming it into an instrument of cultural preservation, identity assertion, and resistance against Euro-Canadian values.

The ongoing use of CAS, especially among younger generations, highlights a collective commitment to preserving and rejuvenating this incredible piece of cultural heritage. The integration of CAS into modern contexts underscores its importance as a living, breathing element of cultural identity.

Through traditions, songs, and stories passed down in Syllabics, and through the profound literature of individuals like Mitiarjuk Nappaaluk, CAS connects the past with the future. In the face of globalization and homogenization, CAS stands as a beacon of resistance, resilience, and renewal.

Inuit elder, Clyde River, Nunavut Canada. 2013.

(Peter Prokosch, edited by Marvin Nauendorff.)

Inuit mother carrying her child, Clyde River, Nunavut Canada. 2013.

(Peter Prokosch, edited by Marvin Nauendorff.)

The Current Situation

While some communities have shifted towards the Latin alphabet, others continue to embrace CAS. The standardization of Inuktitut Syllabics in 1976 marked a significant step in its preservation, blending ancestral languages with global communication. It facilitated a uniform approach to literacy and supported bilingual education.

CAS is present across Canada's northern landscapes, from road signs to official documents. Additionally, CAS has official recognition in some regions. This reflects its enduring significance and the cultural and linguistic inclusivity these symbols represent.

This map showcases the spread of the three principal syllabic writing traditions: Algonquian (black), Inuktut (blue), and Dene Syllabics (brown). It also highlights the historical Blackfoot Syllabics system (grey).

(Map created by Marvin Nauendorff, with data sourced from Typotheque 2022.)

CAS's accessibility is truly remarkable, offering a quick and intuitive learning experience that opens doors to language revitalization, especially for those rekindling connections with their ancestral languages. However, most educational resources and classes predominantly utilize the Latin alphabet, relegating Syllabics to more advanced learning stages. This might be a missed opportunity, given CAS's potential to make language learning more approachable from the start. Adding to the challenge, the language faces a gap in vocabulary for modern concepts, such as those related to COVID-19 or modern technology, complicating its application in teaching contemporary subjects. Even when new terms are coined by commissions, comprehension hurdles emerge if learners are unfamiliar with the original words from which these terms derive. The Avataq Institute is actively addressing these gaps, but financial constraints in the Canadian government's budget have hampered the initiation of new projects or commissions aimed at updating these languages for modern contexts, further complicating the revitalization efforts.

Challenges Along the Way

The creation of Canadian Aboriginal Syllabics (CAS) revolutionized Indigenous literacy in Canada. It offered a straightforward way to capture the nuances of several languages across territories. Its simplicity was not just about ease; it also empowered communities and enabled them to take their education into their own hands. With CAS, anyone could become a teacher, transforming living rooms into classrooms and elders into educators.

Our Lady of the Assumption Catholic Church in Iqaluit, Nunavut, showing Syllabic writing. 2010.

(Anick-Marie, edited by Marvin Nauendorff.)

Yet, as times changed, so too did the challenges that CAS faced. Despite the initial popularity of the system due to its simplicity, the dominance of English and French, which use the Latin alphabet, presented significant obstacles. This was further complicated by the scarcity of educational resources in CAS and limited formal support for teaching it. Policies that outright banned or severely limited the teaching of Nêhiyawêwin Syllabics in schools until the 1970s have left lasting scars and restricted opportunities for younger generations to connect with their linguistic heritage.

The advent of technologies like telephones and radios reshaped communication within Indigenous communities, offering quicker and more convenient alternatives to written Syllabics. While new technologies offer the potential to make publishing and teaching in Syllabics easier, this shift, coupled with the global move towards digital communication, has made CAS seem less relevant in a world dominated by English and its alphabet.

Despite these challenges, Indigenous advocates argue that with the right technological integration and recognition, CAS can continue to thrive in the modern era. They stress that the value of Syllabics goes beyond communication. The goal now is to marry this unique cultural expression with technological advancements to ensure that CAS remains an essential part of Indigenous life in Canada, not just a relic of the past.

Efforts for Revitalization

Lately, the role of Canadian Aboriginal Syllabics (CAS) in media and the digital age is at the heart of a vibrant discussion. Creating media representation, the Aboriginal People’s Television Network (APTN) is leading by example. They incorporate CAS into children's programming, much like "Sesame Street" introduces the alphabet to its viewers, blending education with entertainment.

Further solidifying the digital embrace, the inclusion of CAS in the Unicode standard ensures that these scripts are accurately and consistently represented across digital platforms. Building on this progress, Microsoft incorporated Inuktitut and its Syllabics into their translator in 2021, marking a significant milestone in accessibility. Currently, the translator's performance is somewhat limited, often yielding unnatural outcomes, especially with more complex or longer sentences. It also struggles with translating sentences from Inuktitut to English, often omitting crucial details or misinterpreting words. Despite these challenges, the integration of Inuktitut into a digital translating tool represents a remarkable step forward. It highlights the growing accessibility and representation of Inuktitut and CAS in digital spaces, and importantly, sets the stage for continuous improvements to the translator's accuracy and reliability.

While the machine translates the Inuktitut sentence on the left to “One thing that I would like to know is that the skateboarding is very challenging,” the human translation of this sentence is “one thing I really want to emphasize about figure skating is that it’s hard.” It shows that Microsoft Translator still has problems with understanding and interpreting information. This could be due to a lack of source data.

(Graphic created by Marvin Nauendorff with data taken from Microsoft Translator and Nunatsiaq in 2024.)

Linguists and designers are committed to preserving the integrity and authenticity of Indigenous languages. They are providing free resources and refining digital representations of CAS to make sure that Syllabics not only maintain technical accuracy but also resonate with the cultural and linguistic context of Indigenous communities.

Creating typefaces for CAS illustrates a crucial balance between embracing technological advances and honoring Indigenous traditions and preferences. Through these endeavors, CAS is preserved and poised to thrive in the digital landscape. This ensures that Indigenous languages remain a vibrant part of media and technology.

The James Bay Cree of Northern Québec demonstrate the successful integration of Canadian Aboriginal Syllabics (CAS) in both educational settings and daily life. Starting from kindergarten, literacy in Syllabics is emphasized, resulting in high Syllabic literacy rates and establishing CAS as a predominant form of written communication and a benchmark for language preservation. Similarly, in Nunavik, all subjects are taught entirely in Inuktitut during the first three years of primary education. The region has embraced modern technology, using tablets and video games to engage and motivate young learners to embrace and learn the language.

Community support for CAS is strong, highlighting its role in cultural identity and distinguishing Indigenous languages from dominant ones like English and French. This enthusiasm carries over to digital spaces, where youth engagement reflects CAS's relevance in contemporary communication.

Research links Indigenous languages to improved mental health in these communities, underlining the importance of cultural and linguistic revitalization. Innovative uses of CAS demonstrate its practical applications. For example, developing medical materials such as visual acuity charts in CAS can potentially enhance healthcare for Syllabics users.

What Does the Future Look Like?

The preservation of Indigenous languages like Nêhiyawêwin and Inuktitut is vital, impacting both cultural integrity and community well-being. Language loss contributes to cultural erosion and mental health challenges, which highlights the need for integrated language revitalization and public health strategies, such as offering interpretation and intercultural training for public service employees. Additionally, educational challenges, such as the scarcity of Native language teachers and limited Indigenous content in schools, underline the importance of adopting inclusive educational models that respect community values.

“Our language is who and what we are and the health of our language lies at the core of our well-being. ”

Effective preservation efforts recommend policy support for immersion programs, community-led education, and early Indigenous language introduction for children. Emphasizing practical language instruction, and supporting CAS literacy through spoken language improvement, and diverse engagement with CAS can boost CAS literacy. This will make Canadian Indigenous languages more appealing and relevant to learners, thus fostering cultural identity and enhancing community well-being.

In addition, mentor-apprentice models for training language teachers can be implemented. This will link language learning with cultural activities and strengthen connections to Indigenous heritage. Addressing barriers to language preservation requires innovative, respectful approaches that prioritize the linguistic traditions and autonomy of Indigenous communities.

Before It’s Too Late

Inuit hunter feeds his child with still warm meat from just hunted ring seal, Pond Inlet, Canada. 2013.

(Peter Prokosch, edited by Marvin Nauendorff.)

More than just a means of communication, CAS acts as a cultural lifeline and a reflection of the enduring spirit and resilience of Indigenous cultures. Despite facing challenges from historical events, societal changes, and technological evolution, CAS remains resilient. The experiences of communities utilizing CAS offer insightful lessons on the significance of community engagement, the modernization of writing systems, and the essential connection between cultural identity and language revival.

Moving forward, it's vital to keep supporting initiatives such as educational programs, digital advancements, and grassroots revitalization efforts. Recognizing the indispensable role of writing systems like CAS in maintaining the globe's linguistic and cultural richness. The journey of CAS underscores that endangered languages and cultures can not only endure but flourish.

Edited by

Alice Pol, Anthony Burger & Aline Vitaly

Acknowledgements

Naulaq LeDrew (Inuk elder and artist)

Mitiarjuk Nappaaluk (Author of Sanaaq, the first novel written in CAS)

Mary Simon (President of Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami)

Prof. Dr. Lars C. Grabbe (Professor of Theory of Perception)

Cite This Article

Nauendorff, Marvin. 2024. "Script as a Cultural Lifeline - The Untold Story of Canada’s Indigenous Writing System." Linguaphile Magazine, March 23.

https://www.linguaphilemagazine.org/editorial/script-as-a-cultural-lifeline.

Further Reading

Writing the story of a changing North: Sanaaq - An Inuktitut Novel by Mitiarjuk Nappaaluk. By Pauline Holdsworth on CBC Radio, 2023

Nunatsiaq News features a wide variety of articles written in Inuktitut Syllabics and English.

Inuktitut Tusaalanga offers a big number of free online lessons for various Inuktitut dialects.

Bibliography

Brown, J. S. 2014. "Intangible Culture on Inland Seas, from Hudson Bay to Canadian Heritage." Ethnologies 36, no. 1-2: 141–159. Accessed February 7, 2024.

https://doi.org/10.7202/1037604ar.Déléage, Pierre. 2017. "Les écritures des missions de l’Ouest canadien." Anthropos 112: 401-427. Accessed March 15, 2024.

https://shs.hal.science/halshs-03901763.Donovan, Nicola M., and Shelley Tulloch. 2022. "Children’s Acquisition of Literacy in Syllabic Scripts." University of Winnipeg. Accessed February 7, 2024.

https://winnspace.uwinnipeg.ca/bitstream/handle/10680/2057/DonovanTulloch2022_SyllabicLiteracy.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.Dorzheeva, V.V. 2019. "Ethical and Ideological Basis of Canada’s Contemporary Indigenous Languages Policy." In Proceedings of III International Theoretical and Practical Conference “The Crossroads of the North and the East (Methodologies and Practices of Regional Development)”, 29-35. Accessed February 7, 2024.

https://doi.org/10.32743/nesu.cross.2020.29-35.Gagné, C. R. 1959. "In Defence of a Standard Phonemic Spelling in Roman Letters for the Canadian Eskimo Language." Arctic Vol. 12 No. 4 (December): 193–256. Accessed February 7, 2024.

https://doi.org/10.14430/arctic3725.Harper, K. 1993. "Innovation and Inspiration: The Development of Inuktitut Syllabic Orthography." Meta 38 (1): 18–24. Accessed March 15, 2024.

https://doi.org/10.7202/003027ar.Harvey, Chris. 2003. "Some General Aspects of the Syllabics Orthography." Languagegeek. Accessed February 7, 2024.

https://www.languagegeek.com/typography/syllabics/syl1.html.Hawley, Matalin. 2024. "ᐊᔪᕈᓐᓃᖅᓴᖅᑎᑦᑎᔨ ‘ᐅᐱᒍᓱᑦᑎᐊᖅᑐᖅ’ ᐃᓚᒌᑦ ᓄᓇᕗᒥᑦ ᐅᓄᙱᓛᑦ ᐱᒡᒍᓴᐅᑎᔪᓂᒃ." Nunatsiaq News. March 28, 2024.

https://nunatsiaq.com/stories/article/coach-so-proud-of-team-nunavuts/.Kipp, Darrell. 2009. "Encouragement, Guidance, and Lessons Learned: 21 Years in the Trenches of Indigenous Language Revitalization." In Indigenous Language Revitalization: Encouragement, Guidance & Lessons Learned, edited by Jon Reyhner and Louise Lockard. Flagstaff, AZ: Northern Arizona University.

https://jan.ucc.nau.edu/~jar/ILR/ILRbook.pdf.King, Kevin. 2022. "An Introduction to Syllabics Typography." Google Fonts Knowledge. Accessed February 7, 2024. https://fonts.google.com/knowledge/the_canadian_syllabics/an_introduction_to_syllabics_typography.

Langlois, Sophie. 2017. "Enseigner l'inuktitut pour préserver la culture inuite." Radio-Canada. Accessed March 15, 2024.

https://ici.radio-canada.ca/nouvelle/1057959/enseignement-inuktitut-langue-inuit-nunavik.McIvor, Onowa, and T.L. McCarty. 2017. "Indigenous Bilingual and Revitalization-Immersion Education in Canada and the USA." In Bilingual and Multilingual Education, edited by O. García, A. Lin, and S. May. Encyclopedia of Language and Education. Cham: Springer. Accessed February 7, 2024.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-02258-1_34.Mihatsch, Wiltrud. 2007. "Syllabics in Cree and Inuktitut: Signs of Identity." In Colonialism and the Culture of Writing Language and Cultural Contact in Colonial Discourse Traditions, edited by Barbara Frank-Job, Sebastian Thies, and Rosa Yañez Rosales, presented at the 5th Internationale Fachkonferenz der Bielefelder Interamerikanischen Studien. Accessed February 7, 2024. https://www.academia.edu/11334665/Syllabics_in_Cree_and_Inuktitut_Signs_of_identity.

Montpetit, Caroline. 2017. "Le défi de l’inuktitut: conserver la pureté de la langue." Le Devoir. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://www.ledevoir.com/societe/505112/kwe-kwe-les-langues-autochtones-du-quebec.

Murdoch, John. 1981. "Syllabics: A Successful Educational Innovation." Accessed February 7, 2024.

http://hdl.handle.net/1993/9207.National Collaborating Centre For Aboriginal Health (NCCAH). 2010. "Access To Health Services As A Social Determinant Of First Nations, Inuit And Métis Health." Accessed February 7, 2024.

https://www.nccih.ca/docs/determinants/FS-AccessHealthServicesSDOH-2019-EN.pdf.Tungasuvvingat Inuit. 2020. "Why Is Preserving Your Inuktitut Language Important to You?" YouTube video. Accessed March 27, 2024.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Oz0jtICB5-w.Typotheque. 2022. "North American Syllabics Fonts Developed in Collaboration with Indigenous Communities." Accessed February 7, 2024. https://www.typotheque.com/blog/north-american-syllabics-fonts-developed-in-collaboration-with-indigenous-communities.

Wheeler, Winona. 1999-2000. "Calling Badger and the Symbols of the Spirit Languages: The Cree Origins of the Syllabic System." Oral History Forum 19-20: 19-4.

https://creeliteracy.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/calling-badger.pdf.